Des Cowley

synaesthesia: the production of a sense impression relating to one sense or part of the body by stimulation of another sense or part of the body

Nearly twenty years back, I used to visit Mark Harwood's hole-in-the-wall record store Synaesthesia, then located upstairs in a building in Maples Lane, Prahran. He stocked hard-to-get recordings: free jazz labels like FMP, Hat Hut, Winter & Winter, Emanem. Invariably I would stumble upon obscure European releases by Peter Brotzmann, Evan Parker, Cecil Taylor, Steve Lacy and others. Guitarist David Brown was a regular visitor to the store, and I remember coming across him there, always in earnest conversation with Harwood, which is not surprising, given Brown's work with Bucketrider at the time. The music Harwood played in the shop often sounded like some sort of white noise, an ambient transmission made up of a series of electrical bleeps and chirrups, much of it outside my then definition of music, let alone jazz. There are worlds within worlds. Entering Harwood's shop sometimes felt like stumbling upon a hitherto unknown musical continent, which was part of its attraction.

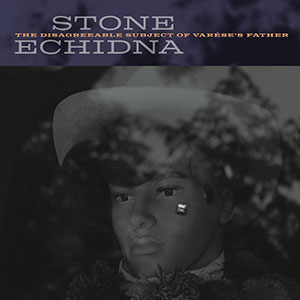

The music of Stone Echidna, with its timbral passages, its emphasis on light and dark shadings, on silence and electro-acoustic impulses, would have been right at home playing in Synaesthesia. The album - appropriately on vinyl - provides the first recorded documentation of the improvising duo of guitarist David Brown and trumpeter Reuben Lewis. The two musicians originally met at the 2014 SoundOut Festival in Canberra, where both were scheduled to play, and later began performing occasional duo gigs. More recently, Brown has been a member of Lewis's psychedelic collective I Hold the Lion's Paw, appearing on the ensemble's debut recording Abstract Playgrounds.

The title of Stone Echidna's debut album might have come straight out of a 1920s Dada performance, or something by Alfred Jarry. In keeping with that anarchic spirit, Varese's Father is an entirely improvised affair. Nothing planned, nothing fixed, just two musicians coming together in a studio surrounded by an assortment of instrumentation: various prepared guitars, pedals, loops, processors, contact microphones, trumpet, amplifiers, objects. It is far from foreign terrain for either musician: think Pateras/Baxter/Brown, or Svelia or the Phonetic Orchestra. In this case, however, we can sense a greater intimacy born of whispered conversation and mutuality. From the opening moments, we intuit the gentle forays these musicians are making, as they embrace uncertainty and abstraction.

Side A's 'lifting the top off folksinging', an uninterrupted seventeen-minute improvisation, is the album's tour de force. There are no hooks, or rhythmic interludes, nothing whatsoever offered by way of a life raft to unfamiliar ears. The piece is crafted as a study in contrasting textures, an investigation into the duality of silence/sound. In its opening minutes, it barely rises above a murmur, but slowly the track's isolated components -acoustic guitar, electronic bleeps, trumpet, effects - coalesce and meld. Brown bends and twists notes into arrhythmic, jerky configurations, while Lewis's trumpet serves up dark and brooding, almost glacial, sounds. As it progresses, spasmodic noises and electronic effects are added, creating an incremental over-layering of ambient textures, and it becomes increasingly impossible to know who is making what sound. For its duration, this tonal world is examined in infinitesimal detail, as if an object were being gazed upon simultaneously from all sides.

Steeped in introspection and deep focus, Stone Echidna has fashioned a musical landscape that demands patience and effort from the listener, asking that we leave our musical baggage at the door, and embrace the unfamiliar. Only with repeated listening does the drama and beauty inherent in this music fully reveal itself.

The remainder of the pieces on the album are shorter in duration, resembling laboratory experiments. Several are the result of single takes; others are offcuts from larger improvisations that can be likened to left-over blocks out of which architectural assemblages might be constructed. Either that or small spontaneous miniatures polished to perfection. They come across as brief tone poems that never outstay their welcome. Varese's Father conjures its own distinct sound world, constructed as real-time aural collages. Brown and Lewis translate isolated sounds into variable patterns, bridging momentum and stasis, tonal reverberation and silence. The end result is a series of sound sculptures, minimal and ambient, hewn out of stone and living matter. Its quiet intensity spills forth, as elemental as breathing.

When I discuss Stone Echidna's influences, Reuben Lewis reels off a series of names unfamiliar to me: Streifenjunko, Eivind Lonning. There are worlds. But, to my mind, this music will reverberate with anyone who has kept an eye on experimental music over the past half century or more: whether it be Roscoe Mitchell's Sound, the early BYG recordings of Anthony Braxton and Wadada Leo Smith, the extended improvisations of guitarist Derek Bailey, Karlheinz Stockhausen's Kontakte, or the music of John Cage.

Who was Varese's father? He appears historically to be a somewhat absent figure. But let's conjure up an image of Edgard Varese instead: wild hair, intense gaze, slightly unhinged. He described his music as sound-masses. In looking to the father, Stone Echidna have embraced the son, responding to the very question he once posed: 'What is music but organised noise?'